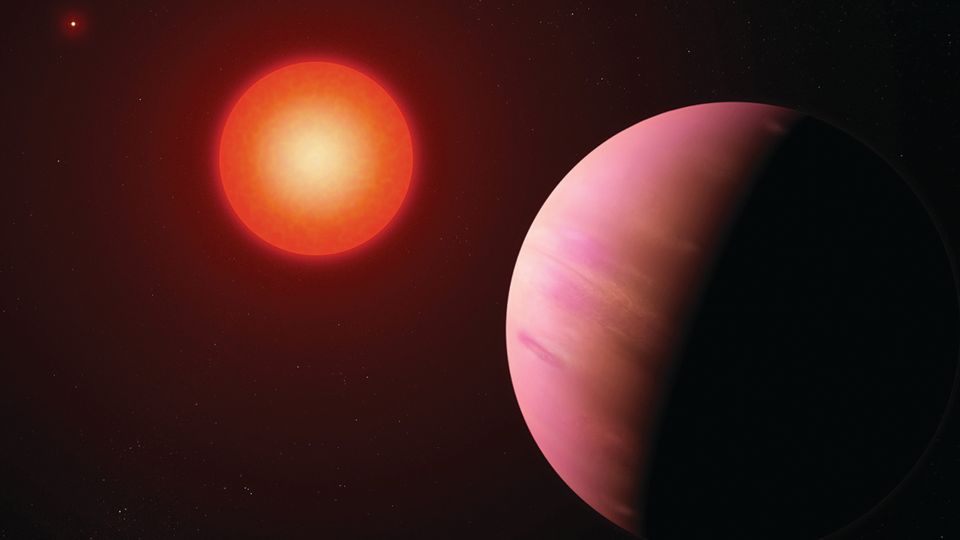

Scientists find surprise 'Water-Rich' worlds orbiting around small stars

A new study suggests that many more planets may have large amounts of water than previously thought--as much as half water and half rock. The catch? All that water is probably embedded in the rock, rather than flowing as oceans or rivers on the surface.

"It was a surprise to see evidence for so many water worlds orbiting the most common type of star in the galaxy," said Rafael Luque, first author on the new paper and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago. "It has enormous consequences for the search for habitable planets."

Planetary population patterns

Thanks to better telescope instruments, scientists are finding signs of more and more planets in distant solar systems. A larger sample size helps scientists identify demographic patterns -- similar to how looking at the population of an entire town can reveal trends that are hard to see at an individual level.

Luque, along with co-author Enric Pallé of the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands and the University of La Laguna, decided to take a population-level look at a group of planets that are seen around a type of star called an M-dwarf. These stars are the most common stars we see around us in the galaxy, and scientists have catalogued dozens of planets around them so far.

But because stars are so much brighter than their planets, we cannot see the actual planets themselves. Instead, scientists detect faint signs of the planets' effects on their stars -- the shadow created when a planet crosses in front of its star, or the tiny tug on a star's motion as a planet orbits. That means many questions remain about what these planets actually look like.

Searching for water worlds

It may be tempting to imagine these planets like something out of Kevin Costner's Waterworld: entirely covered in deep oceans. However, these planets are so close to their suns that any water on the surface would exist in a supercritical gaseous phase, which would enlarge their radius. "But we don't see that in the samples," explained Luque. "That suggests the water is not in the form of surface ocean."

Instead, the water could exist mixed into the rock or in pockets below the surface. Those conditions would be similar to Jupiter's moon Europa, which is thought to have liquid water underground.

"I was shocked when I saw this analysis -- I and a lot of people in the field assumed these were all dry, rocky planets," said UChicago exoplanet scientist Jacob Bean, whose group Luque has joined to conduct further analyses.

The finding matches a theory of exoplanet formation that had fallen out of favor in the past few years, which suggested that many planets form farther out in their solar systems and migrate inward over time. Imagine clumps of rock and ice forming together in the cold conditions far from a star, and then being pulled slowly inward by the star's gravity.

Thanks for visiting Our Secret House. Create your free account by signing up or log in to continue reading.